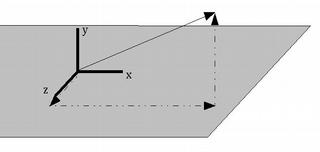

A vector is a direction and magnitude (length). Vectors are used to represent many different things - light source directions, surface orientations, relative distances between objects, etc.

We normally describe a vector as a triplet of (X, Y, Z) values - (vx, vy, vz) represents a vector that points vx units in the direction of the X axis, vy units in the direction of the Y axis, and vz units in the direction of the Z axis.

e.g., (2, 0, 0) is a vector pointing in the direction of the X axis, 2 units long. (1, 1, 0) is a vector pointing at a 45 degree angle between the X and Y axes, 1.414 units long.

The magnitude of a vector (x,y,z) is its Euclidean length - the square root of vx2 + vy2 + vz2.

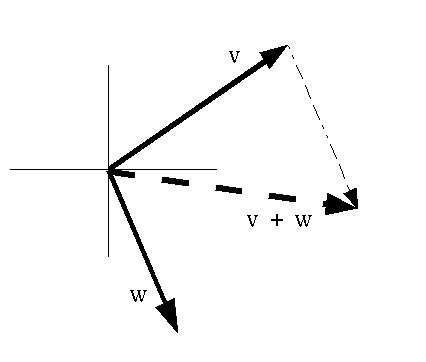

Two vectors can be combined by adding their corresponding components

together.

i.e. (vx, vy, vz) +

(wx, wy, wz) is

(vx+wx, vy+wy, vz+wz

).

Or, written more expansively:

| vx | | wx | | vx + wx | | vy | + | wy | = | vy + wy | | vz | | wz | | vz + wz |

The result is a vector that is equivalent to sticking the vector W onto the end of vector V, and creating a new vector from the beginning of V to the end of W.

A vector can be multiplied by a single number (a "scalar") to change its length without changing its direction.

| vx | | s * vx |

s * | vy | = | s * vy |

| vz | | s * vz |

The dot product of two vectors is an operation defined as:

| x0 | | x1 | | y0 | * | y1 | = x0*x1 + y0*y1 + z0*z1 | z0 | | z1 |The result is a single number, which is equal to the product of the lengths of the two vectors and the cosine of the angle between them.

It can tell us how much two vectors point in the same direction - it is maximum when they point in exactly the same direction, and it's 0 when they're at right angles.

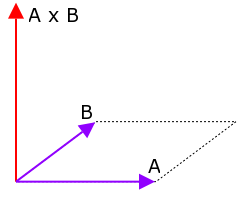

The cross product is a function of two vectors that will produce a new vector perpendicular to both. The length of the cross product is equal to the area of the parallelogram formed by the two vectors.

The formula for the cross product of two vectors A & B is:

[ ( Ay Bz - Az By ), ( Az Bx - Ax Bz ), ( Ax By - Ay Bx ) ]

The Python equivalent is:

def crossProduct(A,B):

return [ A[1] * B[2] - A[2] * B[1],

A[2] * B[0] - A[0] * B[2],

A[0] * B[1] - A[1] * B[0] ]

The direction of the cross product is determined by the right-hand rule applied from vector A to vector B (so if you multiply them in the reverse order, the result will point the opposite direction).

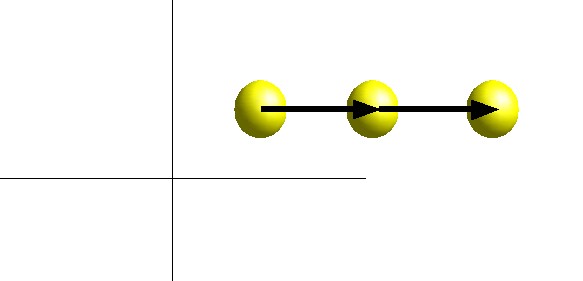

A vector can be used to represent the motion of an object.

The vector indicates the object's velocity - the direction of the vector is the direction that the object is moving, the magnitude of the vector is the speed.

The vector corresponds to how the object will move in one unit of time.

e.g., a velocity vector of (2, 0, 0) indicates that the object is

moving 2 meters/second along the X axis (assuming our units are meters

and seconds).

If it starts at (3, 1, 0), then after 1 second its position will be

(5, 1, 0). After 2 seconds, its position will be (7, 1, 0).

[Note that the choice of units is arbitrary, and is up to you when writing your programs; all that matters is that you be consistent within a program, and not, for instance, try to combine meters per second with miles per hour.]

In general, if an object starts at position P0, with velocity V, then after t time units, its position P(t) will be:

P(t) = P0 + t * V

Creating a vector class allows one to work with vectors more simply.

Vector operations just require a single statement, rather than a loop or separate statements for X, Y, & Z components.

a = Vector((1, 2, 3))

b = Vector((0, -1, 0))

c = a + 2 * b

d = a.dot(b)

Misc functions:

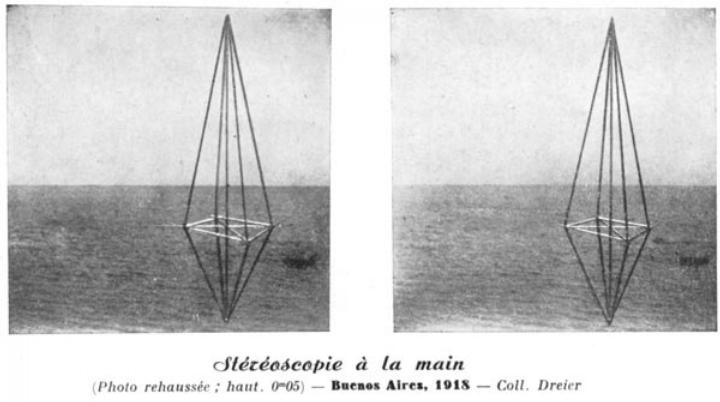

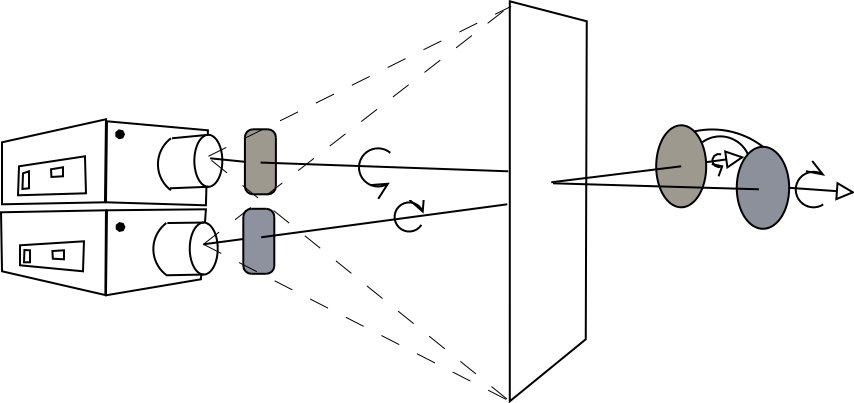

Each eye gets a slightly different view of the world

The brain fuses the two views to get depth information

Create two distinct images - one for each eye

Used since early 1800s

Present each image separately to each eye

e.g. stereoscope, HMD

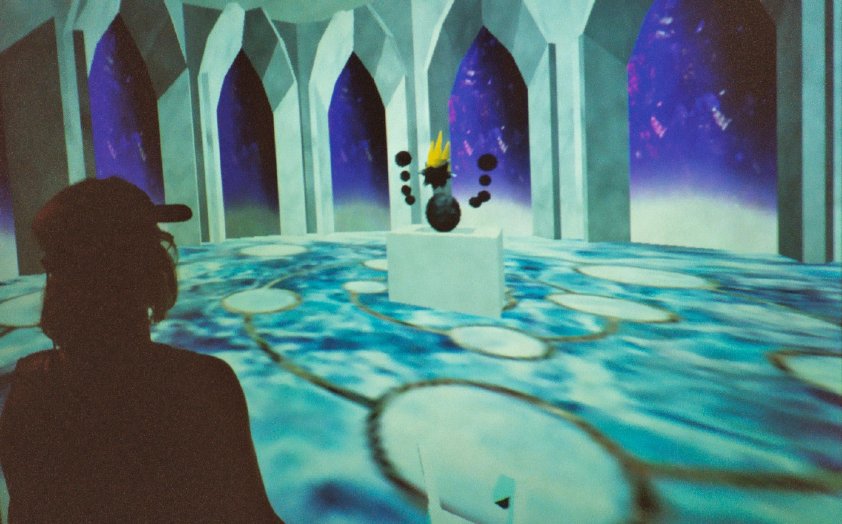

With a projection screen, images must overlap

Glasses filter images - each eye sees only one

Problems:

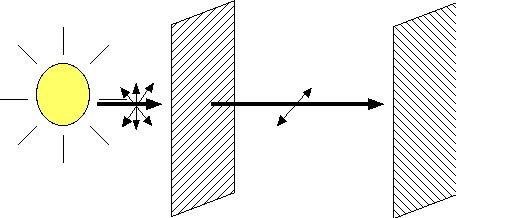

Uses polarization to separate images

Two projectors - one for each eye

Each eye's image is polarized differently

Problems:

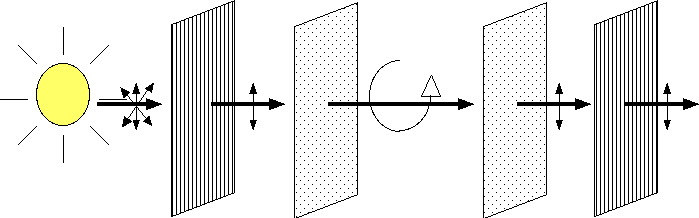

Linear polarizer + quarter-wave retarder = circular polarization

Polarization is left-handed or right-handed

(clockwise or counter-clockwise)

Immune to head-tilt problem

Problems:

Uses colored filters

One image is red, other is blue/green/cyan

Only requires one projector (any type)

Filters make different colors appear at different depths

Red appears close, blue appears distant

Images viewed through dark lens reach brain slower

Pulfrich glasses have one dark lens, one clear lens

When objects move, brain fuses images from slightly different times

Glasses-free

Different eye-views are interleaved vertical strips

Barrier screen blocks all but one image from any viewpoint